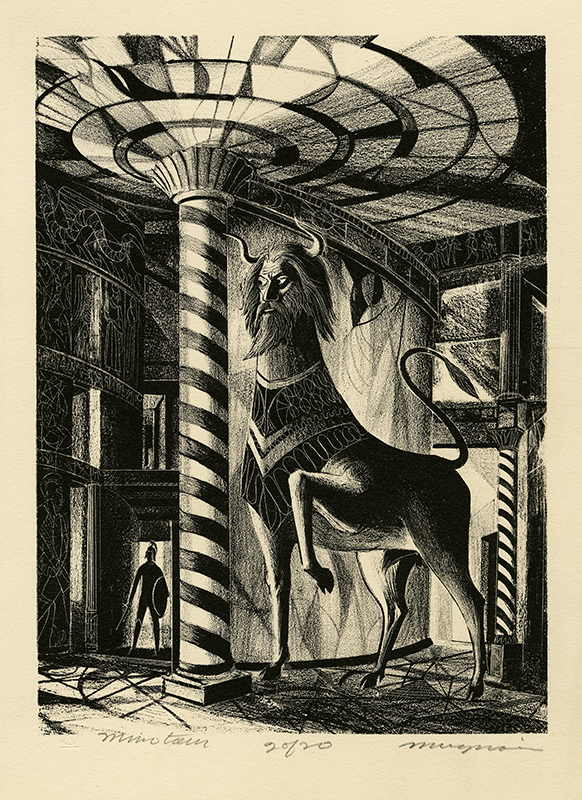

Minotaur is a lithograph from 1953 by American printmaker, Joseph Mugnaini (1912-1992). It is pencil signed, titled, and editioned 2 of 20. It was printed by Lynton Kistler on ivory Rives wove paper and the image measures 8-1/2 x 7-1/4 inches. This lithograph is accompanied by an authentication from Kistler which is pencil signed by Mugnaini. An alternative title for this lithograph is Theseus and the Minotaur.

Minotaur was one of twenty-four lithographs created by Mugnaini to illustrate Bullfinch’s The Age of Fable that was published by the Limited Editions Club. Mugnaini’s images are reversed in the book so his lithographs were photographed and the images transferred to stone or plates for printing in large scale by George C. Miller. Minotaur was inserted between pages 96 and 97 in this book. The lithographs were included in the 1959 exhibition Joseph Mugnaini Prints and Drawings at Georgetown University and Thesus and the Minotaur is listed as number 9 in the accompanying catalog.

The minotaur was a fabulous monster, half-man and half-bull, that was kept by Minos in a labyrinth created by Daedalus. The minotaur was the offspring of Pasiphae, the wife of Minos, and a white bull sent to Minos by Poseidon for sacrifice. Instead of killing it, Minos kept the bull alive which angered Poseidon so he placed a spell upon Pasiphae which caused her to fall in love with the bull. When Minos' son, Androgeos, was killed by the Athenians, Minos demanded that seven Athenian youths and seven maidens be sent every ninth year to be devoured by the minotaur. When the third time of sacrifice came, Athenian hero Theseus volunteered to go. Minos' daughter, Ariadne, fell in love with Theseus and she therefore gave him a ball of thread to unwind to mark his path in the labyrinth and, after killing the minotaur, he found his way out and they escaped together.

Joseph Anthony Mugnaini, painter, printmaker, author, illustrator,

and educator, was born Giuseppe Mugnaini in Viareggio, Tuscany,

Italy, on 12 July 1912. Shortly after his birth his family emigrated to the

United States and settled in Riverside, California. Eleven years later they

moved to Los Angeles and, in 1941, Mugnaini became a naturalized citizen.

He attended the Otis Art Institute in Los Angeles from 1940 to 1942, before serving the U.S. Army during World War II. After his discharge, Mugnaini returned to Otis Art Institute on the G.I. Bill and three months later he joined the faculty of Otis where he eventually became head of the Drawing Department. He retired in 1976.

Author of five books on art techniques and materials, he is best known as being the primary illustrator of the science fiction books of Ray Bradbury. Mugnaini earned an Academy Award nomination and the Golden Eagle Award for his paintings for the film Icarus, a Bradbury collaboration.

Mugnaini was a member of and exhibited with the Painters and Sculptors of Los Angeles, the Los Angeles Art Association, the Glendale Art Association, and the Society of American Graphic Artists. He exhibited at the Los Angeles Public Library, 1947; Chabot Gallery, 1949; Compton Art Center, 1951; Los Angeles County Museum of Art, 1951; Pasadena Art Institute, 1954 (solo); Sierra Madre Public Library, 1959 (solo); and Orange Coast College, Costa Mesa, 1974 (solo). Mugnaini's work was included in the annual National Exhibition of Prints at the Library of Congress and he was awarded the Pennell Prize three years in a row. His works are in the collections of British Museum; Los Angeles County Museum of Art; Norton Simon Museum, Pasadena; University of Hawaii; Temple University, Philadelphia; and the Library of Congress, Washington, D.C.

Joe Mugnaini died in Altadena, California on 23 January 1992.

John C. Tibbetts interviewed Mugnaini and he later described his essence: I will never forget the bristling energy and vitality of Joseph Mugnaini. I can still see him, scowling amiably at me from beneath his hat brim, bursting into hearty laughter and expostulations as he as he talked. His hands were always in motion, and after finding some note paper in my hotel room, he happily scrawled away, the restless lines dashing and skittering across the surface in quick, rapier-like jabs and thrusts. He seemed to be conducting with the pen, as an orchestra leader would gesture and cajole sounds from his players. His dynamic lines seemed to gather themselves of their own accord into forms which coalesced into living images.