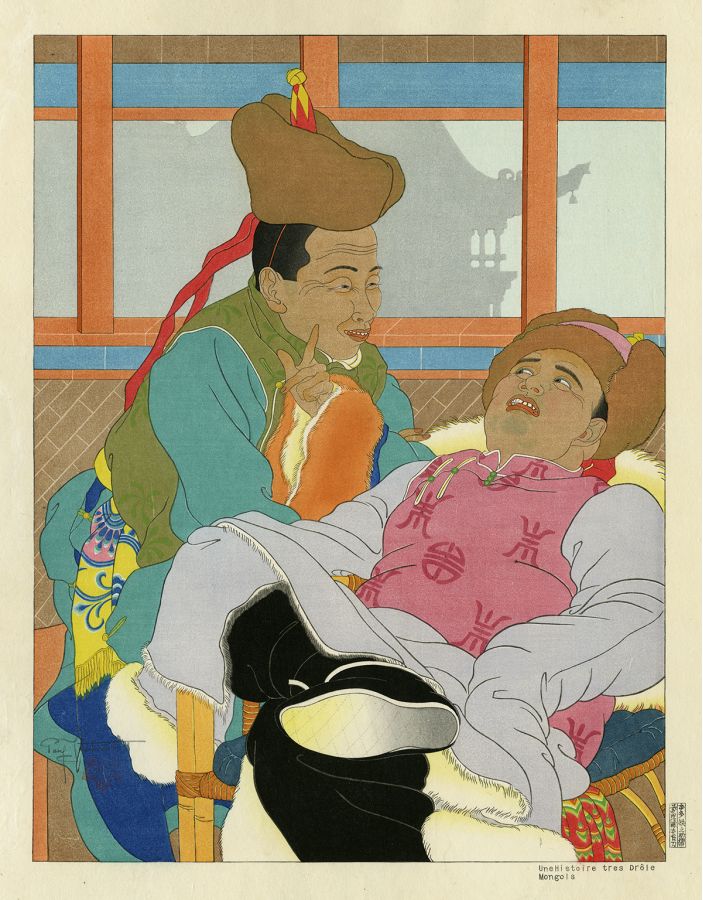

Self-published, second edition 350; numbered '131/350', lower left, verso; Miles 105.

Signed in pencil in the image, lower left, with the artist's red 'Ivy' seal. Seals of the carver, Kentaro Maeda, and the printer Honda, in the lower right margin.

Image size 15 7/16 x 11 3/4 inches (392 x 298 mm); sheet size 18 1/2 x 14 1/8 inches (470 x 359 mm).

A fine impression, with fresh colors, on the artist's handmade, personally watermarked Japan paper, in excellent condition.

Collection: USC Pacific Asia Museum.

ABOUT THE ARTIST

The Yokohama Museum of Art mounted an extensive exhibition of Paul Jacoulet’s graphic art in 2003, the first in Japan. Tai Kawabata, the award-winning staff reporter/writer for The Japan Times, wrote in his review of the show:

“Visitors to ‘The Rainbow Vision of French Ukiyo-e Artist Paul Jacoulet’ will not see traditional ukiyo-e subjects, such as landscapes or beautiful Japanese women. Instead, they will be struck by a large number of predominantly pastel-hued, though vivid — and often erotic — portraits of the indigenous people of Micronesia.

Jacoulet, who suffered from frailty and ill health, first visited Micronesia at his mother’s recommendation in 1929. From then on, until around 1937, he repeatedly wintered in the islands — at that time under a Japanese mandate. What Jacoulet captured in Micronesia was the transient beauty of a paradise on the verge of disappearing — and he used incredible craft and skill to create his stunning images. After the opening ceremony of the exhibition, Christian Polak, an expert on Jacoulet who contributed a biography of the artist to the catalog, summarized the artist’s technique: 'He used only pencils [to draw lines]. He had marvelous pencil lines — they are like Utamaro. His colors are fantastic — they are like Gauguin.'

While traditional Japanese ukiyo-e artists layered on colors by using 20 to 30 blocks per print, according to Polak, Jacoulet used as many as 200 different blocks to create a single print. Thus his works are very much the product of collaboration between the artist himself and Japanese woodblock carvers and printers. Perhaps this explains why, despite a prolific output of drawings and watercolors, Jacoulet produced just 166 colored woodblock prints. Of these, only 26 deal with Japanese subjects. Among other subjects are Koreans in traditional dress, elderly Ainu people, Chinese beauties and Western residents of Japan. Some 100 prints are displayed here.

Born in Paris in January 1896, Jacoulet arrived in Japan in September 1899 when he and his mother joined his father, Paul Frederic, who taught French at the School of Business (now Hitotsubashi University) and the School of Foreign Languages of Tokyo (now the Tokyo University of Foreign Studies). The young Jacoulet completed his primary and secondary education at the Tokyo High Normal School, where he was the only Western pupil. He also learned Japanese calligraphy and took private lessons in Western-style painting with Seiki Kuroda (1866-1924), a Japanese pioneer of the genre. He also took dancing lessons and studied gidayu (narrative chanting to the accompaniment of shamisen), at which he attained almost professional-level proficiency. Under Terukata Ikeda (1883-1921) and his wife Shoen (1888-1917), he also mastered the techniques of bijin-ga (paintings of beautiful women).

Around the beginning of 1915, Jacoulet started working at the French Embassy. In the decade that followed, he began to devote his energy to painting. Jacoulet’s first published prints, which appeared between 1934 and 1935, were 10 works grouped under the title “Genre Prints from Around the World.” The series comprised portraits of seven Micronesians, one Japanese, one Korean and one French woman, and included his first color print, “Young Girl of Saipan and Hibiscus Flowers, Marianas.” This series was followed by numerous prints based on watercolors made during his visits to Micronesia, Korea, and China.

In addition to Jacoulet’s woodblock prints, the current exhibition includes his Japanese paintings, drawings, and watercolors — the latter being shown publicly for the first time. Kiyoko Sawatari, who is the driving force behind the exhibition, examined more than 2,000 of Jacoulet’s watercolors and drawings at the artist’s Karuizawa studio in Nagano Prefecture. “Jacoulet is different from other painters of Japonisme, in that he became an artist in Japan,” says Sawatari. “His work is too complex and multidimensional to be subsumed under the simple phrase ‘a blending of Japanese and Western styles.’ “ That the works survived at all is thanks to Rah Yong Hwan, a Korean who served as Jacoulet’s assistant and secretary and later became a naturalized Japanese citizen, taking the name Hiroshi Tomita.

Just before the March 1945 Tokyo fire-bombing, Tomita and his three younger brothers transported Jacoulet’s works from his studio in Akasaka to Karuizawa. There they survived, and Therese, Tomita’s daughter, who was adopted by Jacoulet, took on the task of preserving his works after the artist’s death. Thanks to the devotion of a small number of enthusiasts, Jacoulet’s work survives today to be seen and appreciated by all.