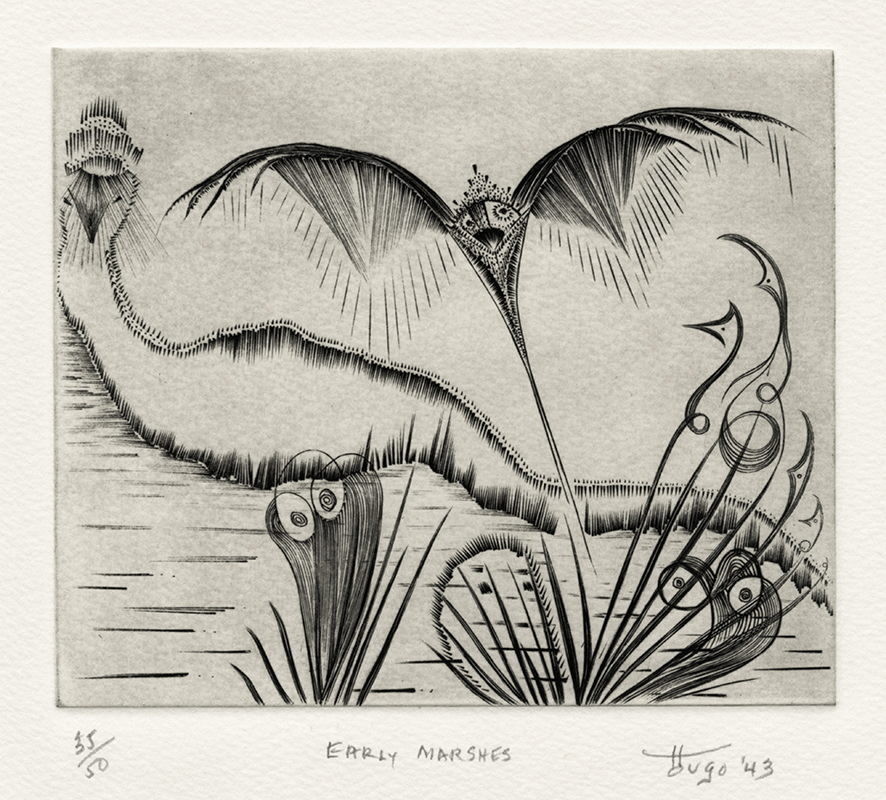

Early Marshes is an engraving originally created in 1943 for the suite Ten Engravings by American artist Ian Hugo. This impression was printed in 1978 by Madeline-Claude Jobrack on ivory Arches wove paper. It is pencil signed, titled, dated '43, and editioned 35/50. This was published in 1978 by Associated American Artists, New York in the suite Ten Engraving: Ian Hugo. The total number of impressions pulled from each plate was 61. Of the regular edition, the first twenty, numbered 1/50 through 20/50, were available as suites. Impressions 21/50 through 50/50 were available individually. There were ten artist’s proofs suites and one printer’s proof suite. The platemark measures 5-7/8 x 4-15/16 inches and the reference for this engraving is AAA 2464.

Early Mashes shows Hugo’s command of engraving; his lines are crisp and energetic and with his lines Hugo created a surreal landscape with humorous, anthropomorphic marsh creatures. In her foreword for Ten Engravings: Ian Hugo, Anaïs Nin wrote: Ian Hugo learned the technique of line engraving on copper at Atelier 17, under Stanley William Hayter, but as an artist he is essentially self taught. These engravings began as unconscious “doodling;” the doodling became an unpremeditated pressure on the engraving tool. Amazing and unexpected figures appeared. The lines have the purity and simplicity of cave drawings. The sign of the true artist is one who creates a complete universe, invents new plants, new animals, new figures to transfer to us a new vision of the universe in which dream and reality fuse. Ian Hugo’s plants have eyes, the birds have the delicacy of dragonflies, their feathers have the shape of fans. Humor is apparent in every gesture. He uses a fine spider web to give a feeling of flight, speed, lightness. The body of a woman reveals the structure of a leaf, a plant. Wings are moving in a world unified by mythological themes. This is an animated world, humorous and levitating, elusive and decorative, which by its unique forms and shapes gives us the sensation of a rebirth, a liberation from the usual, the familiar, a visit to a new planet.

Ian Hugo, printmaker, illustrator, and filmmaker, was born Hugh Parker Guiler in Boston, Massachusetts on 15 February 1898. His childhood was spent in Puerto Rico but he attended school in Scotland and graduated from Columbia University where he studied economics and literature. Guiler was working at the National City Bank when he met and married author Anaïs Nin in 1923. They moved to Paris the following year where Nin’s diary and Guiler’s artistic aspirations flowered. Guiler feared his business associates would not understand his interests in art and music so he began a second life as Ian Hugo. Hugo and Nin moved to New York in 1939 and the following year he began working at Stanley William Hayter’s Atelier 17 established at the New School for Social Research.

Hugo began producing surreal images that often accompanied Nin’s books. For Nin his unwavering love and financial support were indispensable, Hugo was “the fixed center, core...my home, my refuge” (Sept. 16, 1937, Nearer the Moon, The Unexpurgated Diary of Anais Nin, 1937-1939). A fictionalized portrait of Hugo appears in Philip Kaufman's 1990 film, Henry & June.

Responding to comments that viewers saw motion in his engravings, Hugo chose to take up filmmaking. He asked Sasha Hammid for instruction and was instructed, “Use the camera yourself, make your own mistakes, make your own style.” Hugo delved into his dreams, his unconscious, and his memories. With no specific plan when he began a film, Hugo would collect images, then reorder or superimpose them, finding poetic meaning in these juxtapositions. These spontaneous inventions greatly resembled his engravings, which he described in 1946 as “hieroglyphs of a language in which our unconscious is trying to convey important, urgent messages.” In the underwater world of his film, Bells of Atlantis, all of the light is from the world above the surface; it is otherworldly, out of place yet necessary. In Jazz of Lights, the street lights of Times Square become in Nin's words, “an ephemeral flow of sensations.” This flow that she also called “phantasmagorical” had a crucial impact on filmmaker Stan Brakhage who stated that without Jazz of Lights (1954) “there would have been no Anticipation of the Night.” Hugo produced fifteen film between the 1946 and 1979.

Hugo lived the last two decades of his life in a New York apartment high above street level. In the evenings, surrounded by an electrically illuminated landscape, he dictated his memoirs into tape recorders and would from time to time polish the large copper panels that had been used to print his engravings from the worlds of the unconscious and the dream.

Hugo’s works is represented in the collections of the Baltimore Museum of Art, Maryland; the Brooklyn Museum, New York; the Indianapolis Museum of Art, Indiana; the British Museum, London; Museum of Modern Art, New York; Firestone Library, Princeton University, New Jersey; the Rose Art Museum, Brandeis University, Waltham, Massachusetts; the Library of Congress, the National Gallery of Art, and the Smithsonian Museum of American Art, Washington, D.C.

Ian Hugo died in Manhattan, New York City on January 7, 1985.