Written by Earl Retif of Stone and Press Gallery.

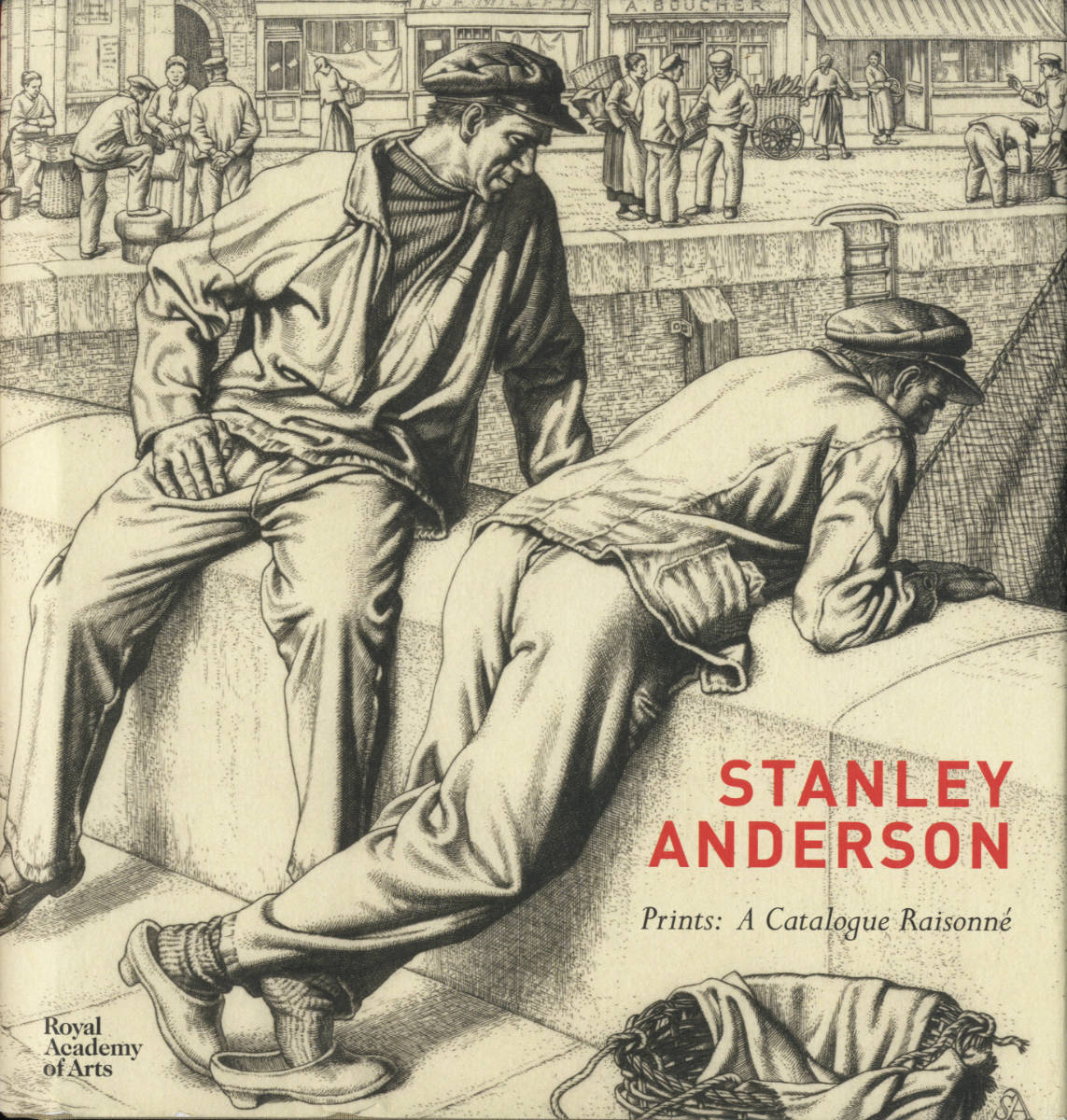

Stanley

Anderson was a shy, modest man not given to bravado or self-promotion in what

he called the “job of art”. He had always heard the calling, but his parents

did not share his ambitious dream. At age 15 he reluctantly agreed to a

seven-year apprenticeship in his father’s metal craftsman business. Anderson

mastered the craft of metal working and this skill served him well when he

turned to engraving as an artistic medium. Anderson was called “old-fashioned”

even by early 20th Century standards because he avoided the innovative art

movements that swept Europe during the late 19th Century and up to World War

II. He studied with Sir Frank Short at the Royal Academy of Art but he was

mostly self-taught from his constant visits to the National Gallery and the

British Museum. Durer, Meryon and Rembrandt were his faculty.

Despite

living through some of the most dramatic changes of the 20th Century, Stanley

Anderson CBE (1884-1966) created a vision of an essentially timeless English

rural tradition in his etchings and woodcuts. He was a master of his craft and

was a key figure in the revival of engraving in the 1920s. Anderson was elected

a fellow of the Royal Society of Painter-Etchers and Engravers. A catalogue

raisonné published by the Royal Academy of Arts gathers together for the first

time the complete oeuvre of Anderson’s prints.

I was only

mildly interested in Anderson’s work but after a visit to the British Museum my

wife and I happened upon a small gallery hanging a retrospective of Anderson’s

work. We were allowed to look but not buy or even reserve. I fell in love with

the clean look and precise nature of Anderson’s engravings and his obvious

preference for society’s underdogs. The gallery owner was adamant that images

would not be for sale until the exhibition formally opened the next day.

Impressions would only be sold on first come first serve basis. I arrived 30

minutes before their 9 a.m. opening but I was third in the queue. The story had

a bittersweet ending. My top images were still available, but the owner limited

the number of pieces I could buy. Apparently, he did not want to have a

month-long exhibition with nothing to sell.

Works by Stanley Anderson available at onpaper.art (click).

In the

following impressions you can sense Anderson’s interest in trust, authenticity,

and the common worker:

The Fallen

Star, #187 in the Royal Academy of Arts’ catalogue raisonné, is a 1929

engraving depicting the Parisian banks of the Seine where “the hair dresser

plying his profession which he was wont to pursue amidst luxurious surroundings

as one of its aristocrats now so humbly al fresco by the riverside…His superior

manner and artistry make their impression on the waiting client watching his operations.”

This image was illustrated in Fine Prints of the Year, 1929.

Parky and

Vurty, Prague, #189 in the Royal Academy of Arts’ catalogue

raisonné, is an engraving in an edition of 85. Anderson’s imagination was

captured by “common scenes and studies of ordinary people such as this aged

street vendor, whom Anderson observed cooking and selling the traditional sausages

that give this engraving its title”.

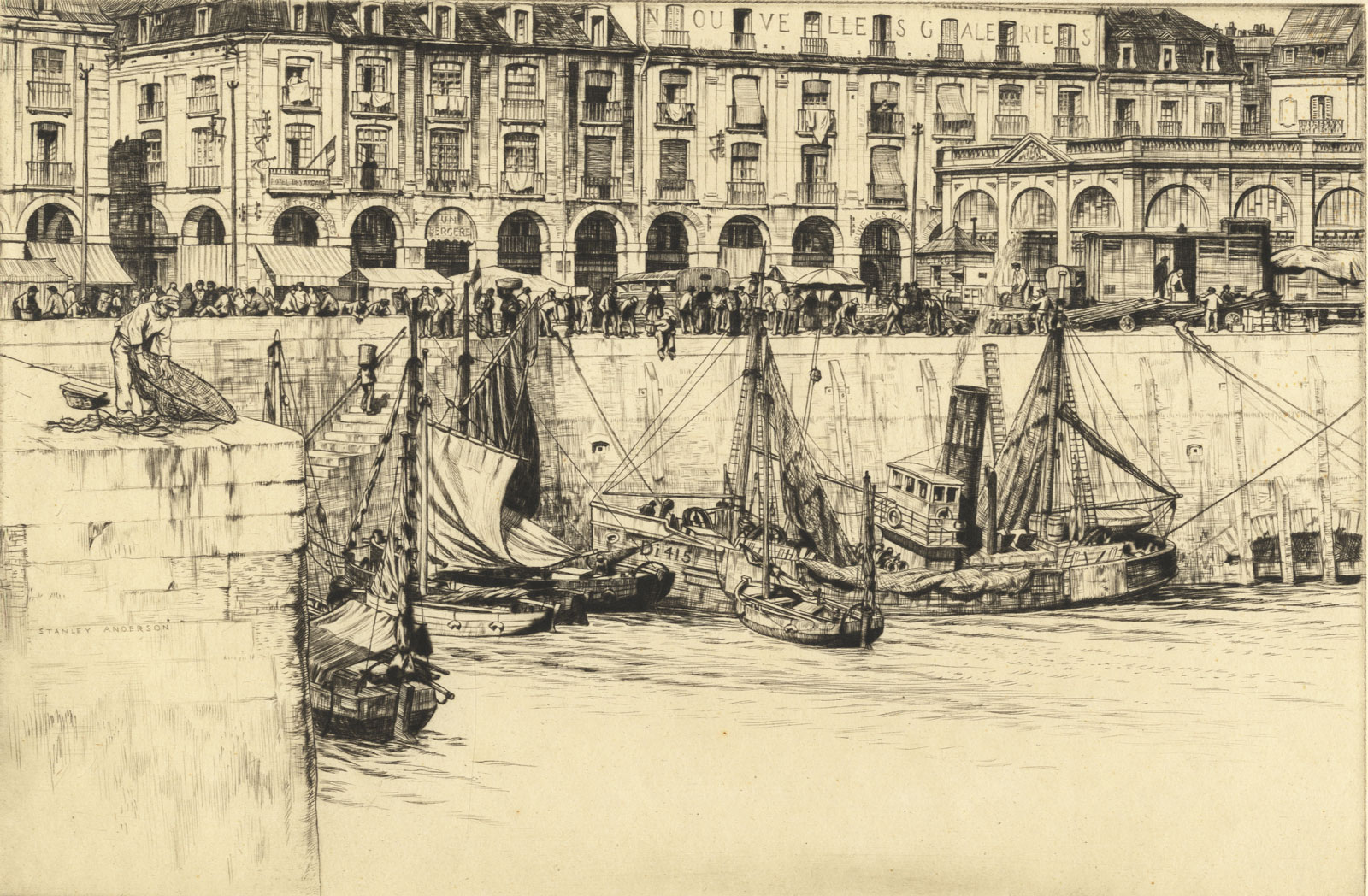

Les

Arcades, Dieppe, Normandy Coast France, #180 in the Royal Academy of Arts’

catalogue raisonné, is a 1928 drypoint in an edition of 80. Malcolm Salmon

wrote “his feeling for architecture was satisfied by the arches and columns of

the arcade, and the lively windows each with its little balconies. His love of

the human crowd finds satisfaction in the fisher-folk and others who line the

quay and animate the scene with their busy idleness.” This image is illustrated

in the Fine Prints of the Year 1928.

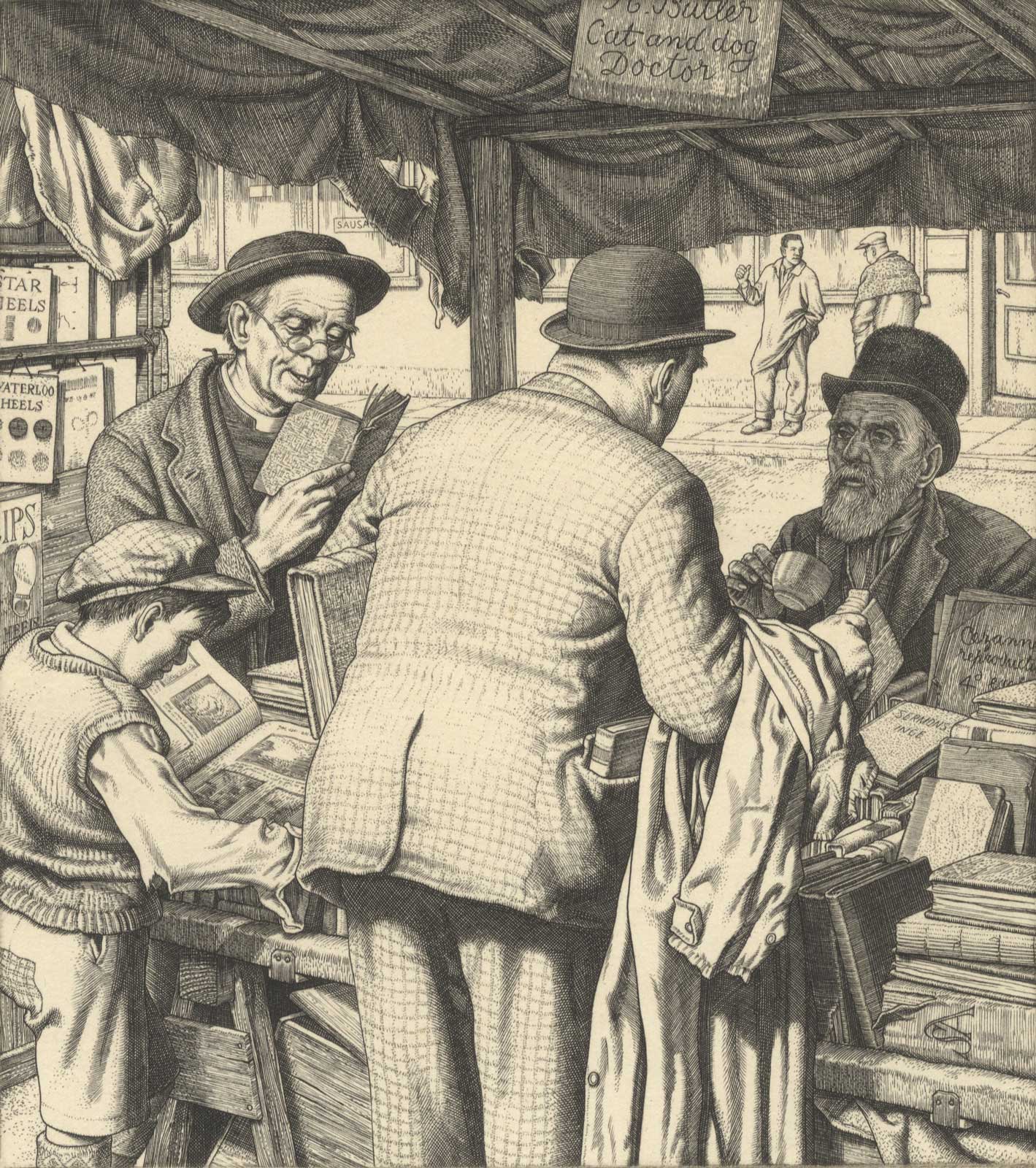

Gleaners # 201 in

the Royal Academy of Arts’ catalogue raisonné, is an engraving in an edition of

60. It’s a look back at a simpler time when patrons jammed London’s Farrington

Road to find the treasures offered by the secondhand booksellers whose stalls

lined that street