Written by Allison Tolman - The Tolman Collection of New York

Toko SHINODA passed away on March 1, 2021, a few weeks shy of her 108th birthday. She only stopped releasing her paintings to the public a few years before her death and, up until the end, living on her own in the duplex apartment where she had lived for years, in the center of Tokyo's chic Minami Aoyama district -- her living quarters on the lower floor and her studio right upstairs. She remained very active, especially considering her age, although she had a "moving chair" installed when she turned 107 so that she didn’t have to navigate the stairs anymore.

Though a woman of contemporary ideas, Toko-san always wore traditional kimono when we met. Each time I visited her, she wore a different one and, when complimented, always remembered the exact provenance of the piece or the occasion for which she had it made. As often as not she would mention the age of the garment or its design, and I was fascinated to learn that she had all her kimono treated with a special product (from Kyoto of course) that is the equivalent of Scotchgard for kimono. She chose our Tokyo living room during a party to demonstrate this quality by enthusiastically pouring a glass of red wine on her kimono sleeve, totally ignoring the fate of the oatmeal-colored carpet!

Toko-san was at her most relaxed at her country home, with its unobstructed view of Mt Fuji, and spent as many weekends and holidays there as possible. It was a rare honor to be invited for a visit. She used to say that the clear mountain air, the locally grown fruits, and vegetables, and the quiet were all factors that contributed to her well-being and inspired her work. She once mentioned that she would have loved to draw a huge calligraphic stroke in the sky in front of Mount Fuji.

I made a point of visiting her each time I was in Tokyo and always enjoyed our conversations. She was a serious person with many intellectual topics to discuss but Toko-san was also someone with whom to giggle and enjoy a good joke. As a dealer and art aficionado, I admire her work and her career, but she has been an inspiration since I was a teenager on a personal level as well. To have carved out the full and autonomous life for herself that she did, based on what she wanted to achieve artistically (both as an artist and a published poet) is truly admirable, I think - especially in view of her gender, her culture, and the era in which she first aspired to excellence and independence, that her uncompromising standards for art and her personal life are clearly illustrated through every brushstroke of each painting or line in any print.

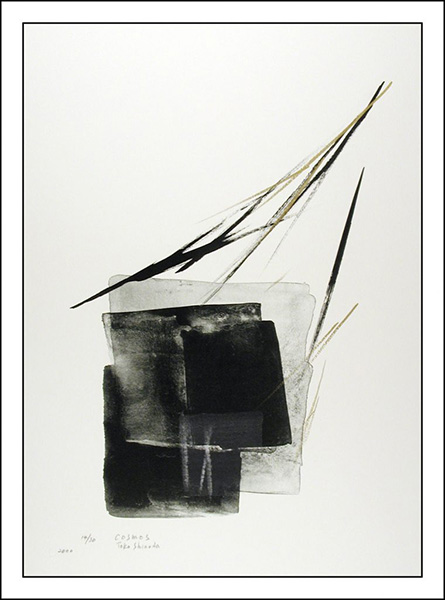

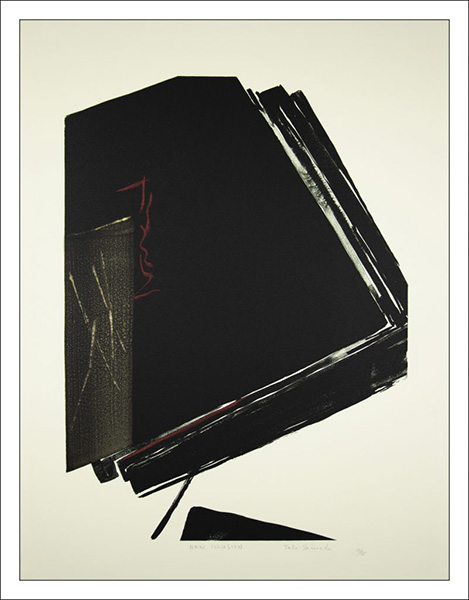

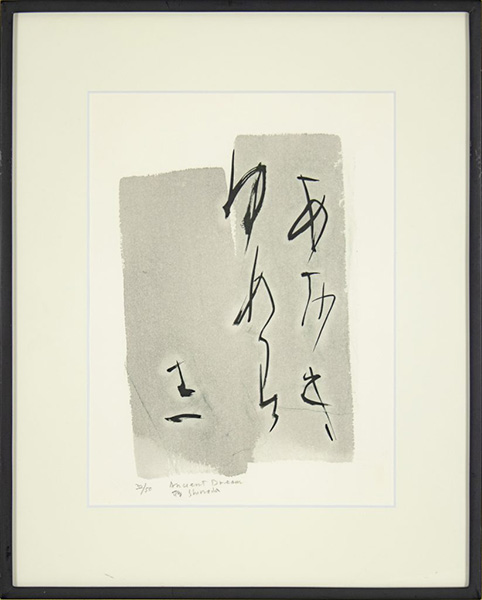

Toko-san worked in both lithography and in painting; she is well known for both and her exquisite work features in museum collections around the world. Her master printer, Kihachi KIMURA (1914-2014), retired in 2007 and she stopped releasing lithographs at that point in time. Her lithographs were masterful in terms of technique and composition and differ from many in that she very often added colorful calligraphic strokes by hand afterward. This means that each of the prints in one of her very small editions was slightly different than the others as opposed to most lithographs where all the prints in an edition are exactly the same if printed properly.

Whether in Tokyo or staying at her house near Fuji-san, Toko-san painted and wrote every single day without fail up until the very end. Some days, it may only have been a few perfectly placed calligraphic strokes. Other times, selecting one of the myriads of brushes in her collection and working on handmade paper, or gold or platinum leaf mounted on board, she would grind some Sumi ink by hand or some cinnabar from her Ming dynasty vermilion tablet and create an enormous work of art, its strength and presence belying her age and slight stature. Toko-san often told me that the area she left blank in her paintings was just as important as the brushstrokes that she brought to life in black, Ming red, silver, gold, or any of a mind-boggling variety of grays. I think that it is because of the intentional breathing room she gave her compositions - the juxtaposition of empty space and deliberate, controlled brush stroke - that her paintings are so vibrant and alive.

Pre-Covid I visited her studio and looked at a number of paintings, both old and new. I could find patterns in her work over a decade, or see how ideas had progressed over time as she developed them, but could not point out which pieces were made when she was 80 or 90 or 100. Her technique and the strength of her work never varied. I find this yet another remarkable fact about a truly extraordinary artist. Those of you who are interested in learning more about her can watch a short film interview here.

I feel grateful and honored that I had her in my life for such a long time. I continue to miss her very much and am so glad that her exceptional paintings and lithographs will be eternal memories of her brilliant artistic legacy.

New York Times obituary, here.

Washington Post obituary, here.

CNN obituary, here.